Aging Baby Boomers and the Generational Housing Bubble: Foresight and Mitigation of an Epic Transition

Abstract

Problem: The 78 million baby boomers have driven up housing demand and prices for three decades since beginning to buy homes in 1970 and continuing up the housing ladder. What will happen when boomers begin to sell off their high-priced homes to relatively smaller and less-advantaged generations?

Purpose: This article presents a long-run projection of annual home buying and selling by age groups in the 50 states and considers implications for communities of the anticipated downturn in demand.

Methods: We propose a method for estimating average annual age-specific buying and selling rates, weighting these by population projections to identify states whose growing proportions of seniors may cause an excess of home selling sooner than others. We also analyze the likely supplier responses to diminished demand, and recommend strategies for local planners.

Results and conclusions: Sellers of existing homes provide 85% of the annual supply of homes sold, and home sales are driven by the aging of the population since seniors are net home sellers. The ratio of seniors to working-age residents will increase by 67% over the next two decades; thus we anticipate the end of a generational housing bubble. We also find that younger generations face an affordability barrier created by the recent housing price boom. With proper foresight, planners could mitigate what otherwise could be significant consequences of these projections.

Takeaway for practice: The retirement of the baby boomers could signal the end of the postwar era for planning, and reverse several longstanding trends, leading decline to exceed gentrification, demand for lowdensity housing to diminish, and new emphasis on compact development. Such developments call planners to undertake new activities, including actively marketing to retain elderly residents and cultivating new immigrant residents to replace them.

Research support: The Fannie Mae Foundation.

| Keywords: baby boomers; aging; housing bubble |

Introduction

The giant baby boom generation born between 1946 and 1964 has been a dominant force in the housing market for decades. This group has always provided the largest age cohorts, and has created a surge in demand as it passed through each stage of the life cycle. As its members entered into home buying in the 1970s, gentrification in cities and construction of starter homes in suburbs increased. Their subsequent march into middle age was accompanied by rising earnings and larger expenditures for move-up housing. Looking ahead to the coming decade, the boomers will retire, relocate, and eventually withdraw from the housing market. Given the potential effects of so many of these changes happening in a limited period of time, communities should consider how best to plan this transition.

Communities in the United States face an historic tipping point. After decades of stability, we expect the ratio of seniors to working-age residents to grow abruptly, increasing by roughly 30% in each of the next two decades. We also expect that this change will make many more homes available for sale than there are buyers for them. The exit of the baby boomers from homeownership could have effects as significant as their entry, though with different consequences.

Recent discussion of the housing market has focused on price escalation and the creation of a housing “bubble” (

Case & Shiller, 2003). During the extraordinary run-up in housing prices from 2000 to 2005, the business pages were filled with concern that this supposed real estate bubble might burst. The meltdown of mortgage markets in 2007, led by the subprime sector, has heightened anxiety about foreclosures and price reductions. Certainly this set of recent developments is cause for concern, but a larger and longer-lasting generational correction looms ahead. The changes in the housing market following the retirement of the baby boom generation could provide a context for local planning and development in the next quarter century that is very different from the last.

Urban planners have special responsibility for championing the longer view, as underscored by

Hopkins and Zapata (2007). “As planners we want to work with constituencies to engage and shape futures, not merely stumble upon these futures as they emerge. To shape futures, we must imagine them in advance and understand how they might emerge” (p. 1). Most plans have time horizons of 5 to 20 years.

Nelson (2006) recently called for planners to take the lead in adopting a longer view, asserting that the built environment will be wholly remade in the next half century, and urging planners to place their incremental decisions in this longer perspective. Such a long-term outlook is very different from that of business forecasting, which typically informs real estate market analysis. Such forecasting rarely looks beyond 1 year.

1

Analyzing the implications of demographic trends driven by human aging can help planners envision the changes ahead (

Masnick, 2002;

Myers & Menifee, 2000). The aging of the baby boomers has been foreseen for decades, but was for many years too distant to cause much concern except about its possible consequences for Social Security. The passage of time has brought the issues closer, and it may now be appropriate for urban planners to emphasize the broader implications of this major demographic change. Only a few planners have considered what an aging society might mean for transportation, land use, or other planning concerns (

Giuliano, 2004;

Rosenbloom, 2004). The first wave of baby boomers will reach age 65 (the dividing point between what we term “elderly” or “seniors” and working-age adults) in 2011, with the last of this generation scheduled to cross that threshold in 2029. Meanwhile the ratio of seniors to younger adults will surge to unprecedented levels, affecting all aspects of community life in which these two groups are systematically different.

We consider the implications of this transition by viewing it through the lens of homeownership. One key question is whether the growing numbers of seniors will generate more home sales than the housing market is able to absorb. Specifically, we aim to identify the point at which boomers will begin to offer more homes for sale than they buy, with potentially serious consequences for the housing market. We project when this will occur in all 50 states, taking into account each state's age specific population growth and prevailing patterns of home buying and selling.

We begin by discussing the recent boom in housing prices and the growing gap between an older generation with high housing equity and a younger generation who find housing increasingly unaffordable. We review the notion of a housing price bubble and consider whether a generational housing bubble might exist. We present the age-specific annual rates of buying and selling homes in each state, and use them to create long-term projections. Finally, we discuss the planning implications of these possible futures.

Background

Aging Baby Boomers and the New Dominance of the Elderly

Since it began, the giant baby boom generation has been a dominant factor shaping housing markets. Frequently described as resembling a pig passing through a python, this large bulge of population surged slowly through the age structure. We focus on the adults most likely to own homes by excluding all those age 24 and younger.

2 After 1970, the leading edge of the baby boomers turned 25 and entered the market for homeownership.

Figure 1 shows growth in the U.S. population over seven decades, both overall and partitioned into those between ages 25 to 64 and those 65 and older.

Figure 1 shows that in all decades save the 1960s, a single age group, the leading edge of the baby boomers, accounts for half or more of U.S. population growth.

Between 1970 and 1980, as the baby boom children came of age, the population age 25 and older increased by 22.9 million, more than twice the growth of 10.6 million witnessed between 1960 and 1970. Whereas the largest adult growth in the 1960s was in the group aged between 55 and 64, growth in the 1970s in the 25 to 34 age group was four times greater, and many of these individuals were forming new households and buying homes. This sudden surge in demand drove several housing market trends, spurring new apartment construction, gentrification in cities where young adults congregated, and escalation in house prices in metropolitan areas where increased supply was limited by topography or regulatory constraints. In subsequent decades the leading edge of the baby boom advanced to progressively older age groups, each time contributing half or more of the total population growth in that decade. As the cohort grew older and achieved their peak earnings, they increased demand for move-up housing for families with older children and higher amenity housing for empty nesters with mature tastes.

Figure 1. Growth in United States population age 25 and over for each decade from 1960 to 2030 (in millions): Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2003b, Tables 12 and HS-3.

Figure 1. Growth in United States population age 25 and over for each decade from 1960 to 2030 (in millions): Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2003b, Tables 12 and HS-3. After 2010 the leading edge of the boomers will pass age 65 and growth among the elderly population will substantially exceed that of younger adults, an unprecedented social and economic development. This is best seen in the ratio of those aged 65 and older to working-age adults (aged 25 to 64). After decades of relative stability, this ratio will surge 30% in the 2010s and a further 29% in the 2020s (

Myers, 2007), altering the balance to which we have long been accustomed. Here, we emphasize how this surging ratio will increase the number of older home sellers relative to younger home buyers, and focus on deciphering what this age shift implies for trends in homeownership, and what responses are possible for planners. Although the phenomenon affects every state (

Frey, 2007), its effects will vary somewhat across the nation. For example, from 2010 to 2030, the ratio of seniors to younger adults is expected to rise 59.0% in New Jersey, 64.0% in Ohio, 66.4% in California, and 82.4% in Arizona, a magnet for retirement migration. (For details on every state see the Appendix.)

Demographics and Housing

Relations between age and housing demand are central to studies of demographics and housing (

Myers, 1990). Housing demographers focus especially on age because mobility declines sharply with age, and because different age groups typically occupy different types of housing (

Clark & Dieleman, 1996;

Gober, 1992;

Masnick, 2002). Of greatest relevance to this analysis are the interactions between age and homeownership (

Chevan, 1989). Homeownership rates rise with age, and do not generally peak until after age 65.

John Pitkin's (1990) study of elderly homeownership was especially notable for showing how most variation in homeownership among older age cohorts over time is explained by demographic factors and inertia from prior decades, while current economic factors add small but significant effects at the margin.

The experience of two Harvard economists, one who later became chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, suggests it is dangerous to attempt to predict long-term trends in housing, unless the demographics are well handled.

Mankiw and Weil (1989) predicted a 47% decline in house prices during the 1990s, based largely on their modeling of declining demand as baby boomers aged. Instead, we have seen baby boomer demand for housing grow and prices double. Housing economist Karl Case recently called the Mankiw-Weil prophecy “one of the worst forecasts in the history of mankind” (

Carmichael, 2007, p. 2). Their approach used cross-sectional analysis improperly to predict trends for age cohorts.

3 Although economists have avoided long-term forecasts since Mankiw and Weil's experience, longitudinal inferences about housing demand can still be made with cross-sectional data if we are careful (

Myers, 1999). Indeed, planners should attempt careful, forward-oriented analysis so as not to make major policy errors and to avoid either undue pessimism or unwarranted optimism (

Krainer, 2005).

Short-Term Correction and a Generational Housing Bubble

We argue that the United States is currently experiencing a short-term housing market bubble that is nested within a longer-term, generational housing bubble of greater magnitude. The recent housing price boom has been remarkably strong. From 2000 to 2005, the median sales price reported by the National Association of Realtors rose 48.6% nationwide, and in some areas, such as California, the median sales price rose 117.1%. Only in 2007 did prices begin to slip in particular metropolitan areas and nationwide. This price run-up had a two-edged effect that substantially increased the home equity of existing homeowners while at the same time making housing less affordable for would-be home buyers. The result is a sharply increased generation gap, with the baby boomers largely gaining, while members of younger generations face higher affordability hurdles.

Short-Term Housing Cycles

According to

Case and Shiller (2003), the term housing bubble “refers to a situation in which excessive public expectations of future price increases cause prices to be temporarily elevated” (p. 299). In a housing bubble, expectations of price appreciation feed further escalation of prices; people buy houses for “future price increases rather than simply for the pleasure of occupying the home. And it is this motive that is thought to lend instability to bubbles, a tendency to crash when the investment motive weakens” (

Case & Shiller, 2003, p. 321).

Underlying the increases are changes in market fundamentals, or what

Shiller (2005) calls “precipitating factors”: increases in employment or income in the area, increases in population, reductions in financing costs, or reductions in land permitted for development. Over the long run, housing construction is closely linked to growth in population, though it can be constrained by recession or by regulatory constraints. There are also substantial lag effects, and the age group experiencing the most growth disproportionately influences the type of housing constructed (

Campbell, 1966).

Regulatory Effects

A number of economists have recently addressed the price effects of regulations that restrict new construction (

Glaeser, Gyourko, & Saks, 2005;

Green, Malpezzi, & Mayo, 2005;

Quigley & Raphael, 2005). Local activism to protect the environment and protect local livability has caused many communities to add development restrictions since 1970 (

Fulton, Shigley, Harrison, & Sezzi, 2000). This was especially true in California, where population grew rapidly in large metropolitan areas, but surrounding water and mountains set physical limits to urban expansion and were protected as resources.

Over the years, both demographic pressure for more housing construction and regulatory restrictions increased. When demand increased during expansionary phases of the business cycle and was not met quickly by increases in supply, housing prices surged. The corrections that followed were rarely as large as the price surges, amounting most often to a few years of price stagnation, not sizable busts, and thus prices have ratcheted upward over the long term.

4

Role of Young Adults

The numbers of young adults in the population and their home-buying behavior are especially important in driving these price trends. They make up the principal reservoir of new demand in the marketplace, a pool of first-time home buyers poised to enter the market or not, depending on perceived conditions. When market fundamentals drive housing prices up, word of mouth and the fear that rising prices will make future purchases unaffordable amplify the trend. As a result, the number of buyers in the market increases to include both speculators

5 and young adults accelerating their entry into homeownership. Thus, paradoxically, because of the investment incentive, homeownership generally rises when housing prices are rising rather than when housing is becoming more affordable. A study of changing homeownership rates among young adults in the 1980s and 1990s found that in states where prices had increased substantially, homeownership rates declined very little or even rose, whereas in states where prices had declined markedly, homeownership rates plunged by 10 to 20% (

Myers, 2001).

6 Potential buyers in declining markets had an incentive to wait for prices to bottom, while those in booming markets felt pressure to accelerate their purchases, to get on board before the train left the station. Thus the housing market's volatility is amplified by buyers' responses to trends in market fundamentals.

Housing markets depend on the ability of the young to buy homes, but they face greater challenges in some parts of the nation.

Figure 2 shows, for each of the states, the ratio of the median value of all owner-occupied homes to the median income of households with heads between the ages of 30 and 34 in 2000 and 2005.

7 This ratio allows us to compare housing prices in different places and over time, and focuses attention on the potential buying power of the generation entering the housing market. House prices in New Jersey nearly doubled, for example, going from 2.89 times the median household income of this group of young adults in 2000 to 5.00 times their income in 2005. Although prices increased in virtually every state between 2000 and 2005, the spikes in some states are clearly evident. The already high-cost states of California and Hawaii became nearly twice as expensive between 2000 and 2005, with median housing value increasing to roughly 9 times the median income of young adults. A second tier of expensive states, with ratios of 5 or greater, includes Nevada in the West and Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New Jersey in the Northeast. A third grouping has ratios greater than 4 in 2005: Arizona, Colorado, Oregon, and Washington in the West, Florida and Maryland in theSouth, and Connecticut and New York in the East. Much of the nation, however, still had low ratios of housing prices to incomes, even after the boom years.

Figure 2. Ratios of median home values to median incomes of household heads aged 30 to 34 in 2000 and 2005, by state: Sources: U.S. Census Bureau (2003a, 2005a).

Figure 2. Ratios of median home values to median incomes of household heads aged 30 to 34 in 2000 and 2005, by state: Sources: U.S. Census Bureau (2003a, 2005a). The Generational Housing Bubble

The current gap between generations has grown unsustainable, and the risk of a generational housing bubble now compounds the risk of a shorter-term housing bubble. The recent upsurge in prices is so extreme in many states, and has been so abrupt, that many real estate observers fear a sharp downward correction.

8 Not only do increased housing prices pose a particular challenge to young households entering the market, but also financing terms became much less favorable after 2005. What have not been recognized to date are the grave impacts of the growing age imbalance in the housing market. If the elderly are more often home sellers, and are more numerous than the young who are buyers, a market shift could come on quickly after 2010, causing housing prices to fall. Even if prices remain flat, without the investment incentive young households will likely slow their entry into homeownership, worsening the imbalance between sellers and buyers. Once past the tipping point, market adjustments will cascade in virtually every community, as the ratio of seniors to working age adults will increase for the greater part of two decades.

New Data on Buying and Selling by Age Groups

Those aiming to anticipate the future of housing markets commonly extrapolate trends obtained by comparing homeownership rates and numbers of homeowners at two different times. Yet these indicators compare housing stocks at different times rather than flows of annual activity. The stock of housing would adjust only gradually even if the annual flows changed abruptly, and thus is not a very sensitive indicator. In fact, even if the number of homeowners remained constant over time, demand would exist for trading up and trading places. Thus, homeownership rates are insufficient for understanding the future of housing markets, and could be misleading.

Instead, we use annual per capita rates at which people of differing ages sell and buy homes, to allow us to project what will happen to the housing market as the demographic profile of the nation changes. These rates are estimated for the period 1995 to 2000, under the assumption that this period yields an expression of more normal market behavior that can be expected to prevail in future years than behavior in the boom years of 2000 to 2005 or the recession years of 1990 to 1995. Sales rates are difficult to know because sellers relocate after they sell and cannot be surveyed. As a result, far more is known about recent buyers. But to understand the market, we need comparable information about both buying and selling. Thus we employed a new method.

We began by assembling 2000 Census sample data for individuals. Our data represented the complete Census sample for each 5-year cohort between the ages of 15 and 85 and older, in each state. We also knew whether these individuals were householders (the persons owning or renting the unit where the household lives), their housing tenure in 2000, the length of time they had lived at their 2000 residence, and the state where they had lived 5 years earlier. We estimated the number of home purchases between 1995 and 2000 in each age cohort, for each state, as the number of householders who were also homeowners and had occupied their homes for less than 5 years, adjusting for those who purchased more than one home for occupancy in this interval. We estimated the number of home sales, again for each age cohort, for each state, in two ways. First we assumed that home buyers were also previous home sellers, after adjusting for the estimated share that are first-time homebuyers (as derived from the American Housing Survey). We assigned their sales to the states where they had reported residing 5 years earlier, whether or not that was where they had purchased a new home. In addition, for those over age 60, we compared the number of homeowners in 2000 to the number of homeowners in the same cohort when it was 10 years younger in 1990. We considered this difference to be a measure of all the home sales that were not followed by purchasing another home, but by renting, moving to a retirement home, or death.

To use these rates of purchase and sale with population projections, they must be estimated on a per capita, not per household, basis. Thus we divided the purchases and sales in each age group for each state over the decade

9 by the average size of the cohort during the decade, and then converted this to average annual rates of buying and selling.

10

Figure 3 displays the annualized, age-specific rates of buying and selling homes per 100 people we calculated for the nation as a whole. The highest buying rate (3.6 purchases per year per 100 persons) occurs between ages 30 and 34. From this peak, rates of buying homes gradually decline at later ages. Readers may find it surprising that the per capita rate of home buying remains as high as it does among the elderly. Over 1% of people aged 75 to 79 buy new principal residences in any given year. Nonetheless, the likelihood that a person in this age group will sell an owner-occupied home is more than three times higher than the likelihood that they will buy a home. At age 80 and above the annual rate escalates to nearly 9 home sales per 100 people.

11 However, until age 70 the annual sell rate remains at about 2% per year for a remarkably broad range of ages.

For most of the modern American lifespan the rates of buying and selling are closely related, because most of those who sell a home then replace it by buying another. However, below age 50, buying is more common than selling, and net homeownership rates rise to this point. When people enter their late-50s and early-60s, as the leading edge of the baby boom generation has now done, buying and selling are in balance. Among individuals in their mid-60s sellers come to outnumber buyers before selling dominates among those in their 70s and beyond. Among people of the same age, sellers come to exceed buyers at about age 65 nationwide, but this varies markedly by state, as shown below.

Figure 3. Average annual percent of persons buying and selling homes in each age group, for the United States, 1995 to 2000: Note: On average, 8.8% of persons 80 and older sold homes each year.

Figure 3. Average annual percent of persons buying and selling homes in each age group, for the United States, 1995 to 2000: Note: On average, 8.8% of persons 80 and older sold homes each year. Projections of Future Numbers of Buyers and Sellers in the 50 States

We now apply our estimates of buy and sell rates in each age group to projected state populations in the same age groups to anticipate the future of home buying in each state. This approach assumes that the age-specific home selling and buying rates of the late 1990s reflect long-run average behavior.

12 Although metropolitan regions are generally regarded as the best geographic units for representing housing markets, data limitations lead us to focus on states. Below, we review variations among the states that reflect many of the same differences that we can observe among metropolitan areas and regions in the nation. We then compare projected numbers of home buyers to sellers for the 50 states.

State Variations in Annual Buy and Sell Rates

It is reasonable to expect that rates of buying and selling would not be the same across all states. States with higher overall homeownership rates surely have higher rates of home buying and, later, greater home sales. Also, states with more affordable housing might be expected to have higher rates of home buying among young people.

Although growth in the population of seniors in most states results mostly from people aging in place (

Frey, 2007), a few states are retirement destinations, likely causing them to have higher rates of home buying among older age groups than other states. Conversely, states with cold climates or more congested living environments may find their elderly residents selling homes at earlier ages to escape unpleasant living conditions.

We compare buying and selling in the following states (each shown with its 2005 ratio of median housing prices to median household income among adults ages 30-34 from

Figure 2): Arizona, a retirement state (4.13); Ohio, a midwestern state, low-cost but cold (2.75); New Jersey, a high-cost eastern state (5.00); and California, a western, very-high-cost state (8.65). As predicted above, Arizona stands out for its exceptionally high buy rates, especially at older ages, which reflect its rapid population growth and high retirement in-migration (see

Figure 4). In the other three states home buying rates peak when people are in their 30s and fall as individuals approach their retirement years. However, Ohio, the low-cost state, has home buying rates that are substantially higher among residents in their 20s and early-30s. California, by contrast, has very low home buying rates among its young adults. This is not surprising given that California's extremely high housing prices require young adults to save longer for larger down payments, and advance further in their careers until they earn the higher incomes required to support large mortgage payments. California's buying rates in middle and older ages are somewhat higher than New Jersey's or Ohio's, likely because buying has been delayed. New Jersey has home buying rates among young adults midway between those of Ohio and California, reflecting its intermediate housing prices, but has the lowest rates of home buying among older residents.

Figure 4. Average annual percent of persons buying homes in each age group, for selected states, 1995 to 2000.

Figure 4. Average annual percent of persons buying homes in each age group, for selected states, 1995 to 2000. Turning to home selling (see

Figure 5), Arizona's high rates stand out among middle-aged persons. Since sales by those from outside the state are counted in their previous state of residence, these represent sales by repeat buyers in Arizona.

13Arizona has long had some of the highest residential mobility rates in the nation, and so this pattern of high rates of selling and buying is not surprising.

The patterns in the other three states are even more similar than they were for buying rates. In middle age, about 2% of people sell their homes each year, although the rate is a bit lower in New Jersey, just as it was for home buying in this age range. California's lower sales among young adults follow because they also have lower buying rates. After age 60 or 70, all four states exhibit rising home selling rates that appear roughly similar.

To understand the future home selling of the giant baby boom generation as they reach age 65, we compare net rates of buying or selling at ages 65 to 69 across the states.

Figure 6 displays these rates in a bar graph ranking states within four regions. The states range from Nevada, with a net buying rate of 1.56% per year, to Connecticut with a net selling rate of 1.02% per year.

In general, very substantial net selling prevails among people of this age across the states of the Northeast and Midwest. In the South, only Maryland and Louisiana have similar rates of net selling, while Florida has very substantial net home buying at ages 65 to 69, far ahead of its closest southern rival, South Carolina. In the West, only California and Alaska have substantial net home selling among people aged 65 to 69. Most of the other western states, led by Nevada and Arizona, have net home buying among people of these ages.

Crossover Point: The Age at Which Selling Surpasses Buying

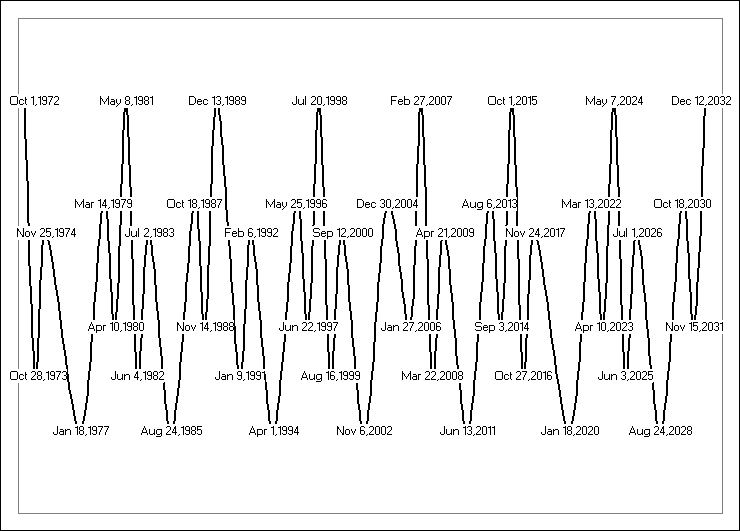

We begin our analysis of the timing of the baby boomers' impact on the housing market by finding the age at which selling typically begins to exceed buying in each state, shown in

Figure 7. In some states the elderly are such active buyers that their growing numbers will not lead to an excess of sellers. In others states, however, the buyers fall behind the sellers at an early age. In six states, the number of sellers begins to exceed buyers at ages 55 to 59, while in seven states sellers exceed buyers at ages 60 to 64. Five of the states that reach this point before age 65 are located in the Northeast and five are in the Midwest, with Alaska, California, and Maryland rounding out the group. Thus, it is a mix of the coldest, most congested, and most expensive states, rather than high-growth states of the South or West, which we expect to lose older homeowners most rapidly. The northeastern states lead the way, and are shaded for emphasis.

Figure 5. Average annual percent of persons selling homes in each age group, for selected states, 1995 to 2000: Note: On average, between 8 and 9% of persons 80 and older sold homes each year in all these states.

Figure 5. Average annual percent of persons selling homes in each age group, for selected states, 1995 to 2000: Note: On average, between 8 and 9% of persons 80 and older sold homes each year in all these states. In 22 states crossover occurs when people are between 65 and 69. Another 15 states, all in the South or West, have crossover points after age 70, occurring latest in Arizona, Florida, and Nevada. This reflects the historically higher rates of migration toward the South and West, and historically higher retirement out-migration from the Northeast and Midwest. If the baby boomers behave similarly at these ages, their effects on the housing market should exhibit strong regional differences.

Net Excess of Sellers Over Buyers in the 50 States

The ultimate number of sales and home purchases by owner occupiers in a given time period is the product of each state's unique profile of buying and selling rates per capita and the forecasted population for each age group at that point. Some states may have high rates but few people in the relevant age groups. Of greatest importance is whether a state has a growing or static population of young adults to absorb the homes its senior population will sell. The worst case would occur where the older population is numerous and sells its homes at an early age, but the young adult population is growing slowly or not at all, and has a low rate of home buying.

We used population projections for future periods to calculate when we expect home sellers to begin to exceed home buyers in each state, and

Figure 8 summarizes the results. Six states have already entered long-term buyer shortages, withseven more to follow in the next decade. However, for 30 states, we do not expect the number of buyers to fall below the number of sellers until well after 2025.

Construction and Market Response

The foregoing analysis centers on the magnitude of the sell-off among owner-occupants who are baby boomers. In fact, buyers will likely appear for every house because the price will be lowered until the market clears. If prices fall low enough, home buying rates may rise, sellers who are able to remain in their homes may decide to keep them, and investors may step in to claim some properties. If rices fall we also expect home builders to scale back on onstruction, reducing the growth in supply. The questionis whether these adjustments will be sufficient to cushion the baby boomer sell-off.

Reasonable observers might view the problem thus:

…in the long run at least, contraction in the real estate industry may mitigate any impacts of overall decreases in housing demand. The question appears to be whether the impacts of the demographics will result more in industry contraction or in declines in value.14

Figure 6. Net annual percent of persons aged 65-69 buying or selling homes, by state and region. Shiller (2007)

Figure 6. Net annual percent of persons aged 65-69 buying or selling homes, by state and region. Shiller (2007) stresses the importance of supplier responses in ending housing booms. Though past failures to appreciate the competition from other new construction have often led to oversupply, he asserts that large development companies today possesses better information and behave more rationally than in prior decades, as

McCue and Belsky (2007) agree. In fact, in the post-2005 housing market, when sales fell and inventories grew, builders exhibited a disciplined response, scaling back production only 6 months behind the decline in sales (

Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, 2007). Unfortunately, that decline was so precipitous that many home builders were caught with greater debt than cash flow.

It is often overlooked that existing homeowners supply five or six times as many homes for sale as do builders of new homes.

15 Existing homeowners' decisions to sell are not professionally managed, but are driven by personal financial, community, and aging-related life-cycle decisions. The many baby boomers facing these same issues in the future could flood the market with excess supply without regard to declining demand.

Undesirable effects could be magnified by the duration of the baby boomer sell-off. Homebuilders are more likely to survive a short-term pullback than a prolonged contraction that requires them to lay off core staff, abandon land contracts, and sell assets. Firms in the construction industry will attempt to keep building homes at some minimal level just to stay in business. For example, after 2 years of job losses totaling 313,000 in the long recession of the 1990s, production in California only fell to 83,341 new units in 1993, still roughly half the previous volume.

Finally, construction is likely to continue because home builders are in the business of serving buyers whose needs cannot be met by the existing inventory. The fact that older people outnumber younger people nationally (see

Figure 1 and Appendix Table A-1) ensures that most builders will try to serve the former by building housing better suited to their needs than what is already on the market. Although the older population will be selling more homes than they buy, better than 1% of them will still buy homes each year. And younger people will still buy homes at three times this rate. People may demand new construction in order to get novel design or to locate in growing areas where supply is insufficient, or in locations with better access to jobs and transit.

Figure 7. Crossover points: ages at which selling exceeds buying for each state: Note: Shaded states are in the Northeast. Buyers and sellers are owneroccupants, and do not include investors or those buying or selling second homes.

Figure 7. Crossover points: ages at which selling exceeds buying for each state: Note: Shaded states are in the Northeast. Buyers and sellers are owneroccupants, and do not include investors or those buying or selling second homes. In sum, supply will be dominated by the actions of aging homeowners who have little ability to postpone decisions, and home builders who cut back as little as possible. Large builders will shift to markets with good growth prospects and scale back their operations elsewhere. Other builders will find niches of underserved demand, particularly among the elderly, even in stagnant or declining markets. Thus we expect the number of properties for sale to grow ever larger, creating a buyer's market, and vacancies to accumulate in less desirable neighborhoods and parts of the nation.

Consequences of a Generational Housing Price Correction

There will be winners and losers in the correction to the generational housing bubble. Many young adults will wait for downward price adjustments to make home purchases more affordable. However the baby boomers were born over an 18-year period, and their housing sell-off could stretch over two decades instead of the typical 3 to 7 years for a housing market correction. Few young adults are likely to wait that long for prices to bottom out before purchasing.

Figure 8. Period in which sellers exceed buyers in each state: Note: Shaded states are in the Northeast. Buyers and sellers are owneroccupants, and do not include investors or those buying or selling second homes.

Figure 8. Period in which sellers exceed buyers in each state: Note: Shaded states are in the Northeast. Buyers and sellers are owneroccupants, and do not include investors or those buying or selling second homes. Members of the baby boom generation themselves who are homeowners could be losers. As home values decline, so will home equity, shrinking retirement savings. For example,

Nothaft and Chang (2004) recently reported that

home equity—the difference between the home value and the amount of mortgage debt on the property—comprised at least 50% of net wealth for one-half of all households. Home equity is not only the single largest component of net wealth for most families, but it is also held by a broader cross section of families when compared with other assets. (p. 2)

Home equity is less important for high-income households, because they hold a disproportionate share of stocks and other investments, but it is especially important for working- and middle-class households. Moreover, equity may be more vulnerable to downturns than in prior decades. The ease of refinancing or obtaining home equity loans has led many middle-class homeowners to already use up substantial portions of their equity. Analysis of recent trends indicates that many more of the soon-to-be-elderly will be heavily encumbered with debt late in life than has been the case in the recent past (

Masnick, Di, & Belsky, 2006). A 25% reduction in home values could erase half the equity of homeowners with large mortgages.

16 Even among those who do not sell their homes, downward reappraisal will erode the equity that would otherwise have supported reverse mortgages or home equity loans (

Edmunds & Keene, 2006). People who intend to retire using these means of extracting income from their wealth must maintain or increase the value of their homes.

Implications for Local Planning

Communities where home sellers are highly concentrated could be adversely affected by the developments we describe. Our analysis compared the 50 states, and yet we know that substantial variation exists within states, with important differences among cities, suburbs, and rural areas. Given that all housing markets are local, we make the following observations about the potential local impacts and their implications for planners.

Where demand falls short of housing supply, property value assessments could fall after increasing for many years, creating municipal budget deficits and playing havoc with fiscal planning. Although it seems wise for states and localities to use current fiscal surpluses to pay down debt and save for later, this is often difficult for local governments to do. In addition, shifts that abruptly make formerly high-priced properties more affordable will create a different set of problems that could destabilize middle-class neighborhoods. We already know that aging homeowners do less to maintain their homes (

Galster, 1987;

Myers, 1984), and under the scenario we anticipate there may be many more such homeowners who are unable to sell. If they rent their homes or sell them to investors at a discount, neighborhoods once largely owner-occupied will have more renters. During the adjustment process many homes could stand empty for long periods, creating neighborhood nuisances. Beleaguered homeowners will put pressure on local officials to protect their former quality of life. Yet there are a number of ways to plan in advance both to mitigate symptoms and to address the root of the problem.

Plan Housing Construction

Anticipating the consequences of an aging baby boom generation should help planners manage the supply of new construction to meet future housing needs and balance the demands of competing interests.

Recognize New Housing and Locational Preferences

After decades of neglect, apartment construction is resurgent in many central cities (

Birch, 2002), meeting preferences for housing that is higher density and more centrally located.

Fishman (2005) has declared this a new “fifth migration” that will focus residential growth in coming decades toward the centers, not peripheries, of metropolitan areas. To date, however, there is little evidence of any net shift of total or elderly population toward central cities (Englehardt, 2006;

Frey, 2007).

Nelson (2006) called for analyzing both housing preferences and the location of existing inventory to determine needs for new construction. Our analysis provides the demographic driver for these needs and preferences in the aging of the baby boom. Our projections support Nelson's conclusion that the existing supply of large-lot homes, largely located in the suburbs, may be sufficient to meet needs through 2025, at least in many parts of the nation. New construction should remedy the current undersupply of units in the more compact central city and suburban environments shown to be in growing demand, especially for aging boomers (

Myers & Gearin, 2001).

Regulate Overall Supply

If the aging baby boomers sell one type of housing and buy another, this could stimulate substantial construction. Since decisions about new construction are generally decentralized, this could lead to oversupplies of housing in many metropolitan areas. The excess vacancies would likely be clustered in localities with older and less-preferred housing. This could reverse the post-WWII pattern in which new construction in the suburbs left vacancies and abandonment concentrated in older central city neighborhoods.

17 Some are already warning of decline in early post-WWII suburbs (

Lucy & Phillips, 2006), but planners should monitor supply and demand conditions in outer suburbs as well. Planners in the near future may contend simultaneously with neglected low-density single-family districts, dwellings left vacant by waves of exiting baby boomers, and controversial proposals for redevelopment at higher densities.

In the past, development restrictions have protected against oversupply, although they have also led to housing price escalation and decreased affordability. A growing movement aims to relax those restrictions in order to facilitate denser development and make housing more affordable. Although these objectives have merit, planners should evaluate the consequences of making such changes in the context of the long-term decline in housing demand predicted here. How ironic would it be if, after years of price run-ups, development restrictions were suddenly loosened in many states just in time for baby boomers' big sell-off? Local and regional planners should manage additions to the supply of housing to avoid a glut as baby boomers age.

Fight the Rising Ratio

In addition to managing the construction of new housing, local planners should work on managing the ratio of seniors to working-age residents directly. Planners should aim to alleviate the potential impacts of large numbers of elderly home sellers while stimulating demand among younger adults.

Plan to Retain Elderly Residents

Frey (2007) has emphasized that most people will age in the same state or metropolitan area where they have lived, though not necessarily in the same community or house. Communities should retain their elderly residents as long as possible to slow the flow of houses for sale. This makes it imperative to develop elderly friendly, vital communities (

Achenbaum, 2005). Rather than encouraging segregation of the elderly in separate retirement institutions, urban designers should foster their social integration into more lively communities, whose essential features include community activity centers for seniors, close-by retail services, and small, easy-access parks for midday socializing. The new movement toward planning healthy cities for active living can also help planners attract and retain elderly homeowners (

Frank & Engelke, 2001), as can homeowner maintenance programs, dial-a-ride transportation services, and mobile meals services (

Gilderbloom & Rosentraub, 1990).

Attract the Young

Planners should also aim to attract younger home buyers by increasing local employment growth, marketing to the “creative class,” (

Florida, 2003) and building a cultural economy (

Currid, 2007;

Markusen & Schrock, 2006). Strategies to improve amenities and urban livability may appeal to some, but families also need practical help with convenient day care, afterschool programs, and better local schools. Workforce housing programs can help young people absorb more of the homes for sale in a community by providing counseling and purchase assistance. It would be more effective to institute such programs early, before an excess of homes for sale tarnishes the community reputation and deters middle-class buyers.

Attract New Immigrants

Fostering the settlement of new immigrants can also stimulate home buying. Immigrants are typically drawn to concentrations of job growth, but have also taken root in places experiencing average job growth or worse (like the populations of Somalis in Lewiston, Maine, and Hmong in Fresno, California). Once a group is established, it may pull in more residents of the same ethnicity. Thus, community development strategies to promote immigrant settlement can help build a base of young residents. Per capita rates of homeownership rise dramatically as immigrants reside longer in the United States, and immigrant populations are growing faster than native-born populations (

Myers & Liu, 2005). As a result, the foreign-born share of the increase in homeowners has roughly doubled each decade since 1980, rising from 10.5% in the 1980s, to 20.7% in the 1990s, and 40.0% in the period 2000 to 2006 (

Myers & Liu, 2005, Table 2).

18 These shares are even higher in several states, exceeding 60% in California, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Illinois, and they will climb much higher after the baby boomer sell-off commences. It is immigrants who will lead many markets out of the current downturn inhome sales and prices.

Invest in the Young

The foregoing strategies merely help one community compete against others for a fixed number of potential home buyers. A longer-term strategy would expand the numbers of home buyers among the younger generation by investing in their human capital development. A state that invests more in higher education not only trains a workforce with greater earnings potential, but also cultivates the next generation of taxpayers and home buyers. Tax dollars invested today in higher education are reported to return benefits two or three times greater than the original investment, in the form of future tax collections on higher earnings (

Myers, 2007). College graduates can also afford substantially higher priced homes. Upgrading human capital among young adults will be especially crucial as the ratio of seniors to working-age adults grows. Previously neglected minority youth will benefit, as will the rest of society, if state and local governments enhance the productivity of all their human resources.

Conclusion: On the Precipice of a New Era

Our analysis depicts a coming generational transition in the housing market that will upset the historic balance of buyers and sellers. Residents in most states are net buyers of homes well into their 50s. The resulting upward pressure on demand by the large baby boom generation will soon peak, and after age 70 they will be net sellers in all except three states.

Mankiw and Weil (1989) may have miscalculated the timing of decline, predicting its beginning 20 years or more prematurely, but the baby boomers will finally start retiring from the housing market. Their demand for housing will begin to contract, and then will decline at an accelerating rate. Boomers will dominate the housing market, as they have through their entire adult lives, when the ratio of seniors to working-age adults soars by 67% in the next two decades. This tilt toward age groups that are net sellers of housing is historically unprecedented, and it challenges planners to foresee and forestall adverse impacts.

The baby boom generation was born over a period of 18 years, and once its sell-off commences, it could dominate the housing market for up to two decades. Planners could lessen the negative consequences of the deflating generational housing bubble by anticipating these long-term trends and initiating pre-emptive programs to retain elderly homeowners, attract young home buyers, and closely monitor additions to the housing inventory to forestall overbuilding.

Planners must adjust their thinking for a new era that reverses many longstanding assumptions. Though planners in many urban areas have been struggling against gentrification, they may now need to stave off urban decline. Whereas decline once occurred in the central city, it may now be concentrated in suburbs with surpluses of large-lot single-family housing. Whereas residential development once focused on single-family homes, many states may swing toward denser developments clustered near amenities. Whereas the major housing problem was once affordability, it could now be homeowners' dashed expectations after lifelong investment in home equity. The new challenge may be how to encourage buyers in distressed environments and how to sustain municipal services in the face of declining property values. All of these reversals result from the aging of the baby boomers. By using foresight, planners have a better chance of leading their communities through the difficult transition ahead.

Appendix

Ratios of seniors to working-age adults, and percent change, by state, 2000 through 2030.

Notes

1. Occasionally housing industry analysts will take a 10-year view. For example, in a recent special effort, a consortium of leading housing trade organizations forecasted the market for a full decade, from 2004 to 2013 (

Berson, Lereah, Merski, Nothaft, & Seiders, 2006). Unfortunately, a 10-year forecast horizon was not long enough for this group, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, or the Economic Development Administration to anticipate the effects of the retirement of the baby boom generation. A 10-year forecast launched from 2007 might now begin to detect these consequences.

2. According to the 2000 Census, only 1.4% of owner-occupied households in the United States were headed by a person under age 25. Age 25 is also generally regarded as the lower boundary of prime working age, when individuals are most likely to hold secure employment.

3. In 1980, the highest per capita spending on housing occurred at age 45; accordingly,

Mankiw and Weil (1989) concluded that once the baby boomers passed age 45 they would begin to spend less on housing, reducing housing demand and lowering prices as the boomers aged. But it turned out that lower spending on housing after age 45 was not a result of older adults cutting back. Rather, members of the generation that was over 65 in 1980 were unlike their younger counterparts in that they had never spent much housing. The fallacy of Mankiw and Weil's reasoning was revealed once researchers followed individual cohorts' behaviors as they grew older (

Pitkin & Myers, 1994).

4. A recent study by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (

Angell & Williams, 2005) reviewed historical housing booms in all U.S. metropolitan areas for which data were available and concluded: “In over 80% of the metro-area price booms we examined between 1978 and 1998, the boom ended in a period of stagnation that allowed household incomes to catch up with local home prices.”

5. Those buying for investment purposes increase their market activity when prices are rising most rapidly and withdraw when prices flatten or decline. For example, between 2002 and 2005, when the recent boom began to crest, the investor share of mortgage originations grew from 6.8 to 10.9% in Los Angeles, from 5.8 to 13.8% in Austin, and from 8.1 to 15.8% in Miami (

Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, 2007, Appendix W-4).

6. There was a very strong positive correlation between changes in homeownership rates among heads of households aged 25 to 34 and changes in median house values for states, with r = 0.75 in the 1980s and r = 0.65 in the 1990s (

Myers, 2001).

7. This ratio is not a representation of the purchase calculation of actual households, but a relative index. In fact, the median income pertains to both renters and owners, and many young buyers are likely to purchase homes below the median price.

8. This is certainly the conclusion of Robert Shiller (2005, 2006), who plots house prices against other asset classes and shows that the recent run-up in house prices is unprecedented.

9. We converted data for the 5-year interval preceding the census to its equivalent for a full decade by summing the experience of adjacent 5-year cohorts. For example, we aggregated 5-year rates for persons aged 35 to 39 in 1995 to 1999 with those for persons aged 30 to 34 in the same time period, synthetically estimating the experience of a full decade.

10. Complete data on estimated buy and sell rates for all 50 states for each of 13 age groups are available from the authors on request.

11. Death rates climb markedly after ages 55 to 64. Averaged between men and women (weighted for the population at risk), the annual probability of death rises to 2.4% between the ages of 65 to 74, 5.7% between 75 and 84, and 15.5% at 85 and older (

U.S. Census Bureau, 2003b). Considering that elderly persons also face higher risks of severe illness or physical incapacity, it is not surprising that they would be two to three times more likely to sell their homes than younger homeowners.

12. The choice of calibration period is important, because the estimated rates of behavior are intended to represent underlying demographically based demand and will be held constant in future periods. For this purpose, we judged the period of 1995 to 2000 to be much better for estimating normal market behavior than the boom years of 2000 to 2005, or the recession years included in 1990 to 1995. Although we expect the annual rates will likely rise and fall in the future, we assume that they will fluctuate around the rates we estimated from the age schedule in the baseline period. Thus we feel our result properly depicts the changes in underlying demographically based demand likely to prevail in future periods.

13. In Arizona, the sell rate without correcting for those who sold before migrating to the state is 4.2 per 100 among those aged 55 to 59, and 2.9 per 100 after making this adjustment.

14. This comment is by an anonymous reviewer of the article.

15. In 2005, the year of peak sales of newly built homes, 1.28 million newly built units were sold and 7.08 million existing homes were sold, a ratio of 5.5 to 1. In the low point of the 1991 recession, 0.51 million newly built homes were sold and 3.22 million existing homes were sold, a ratio of 6.3 to 1 (

Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, 2007, Table A-1).

16. For example, among homeowners ages 50 to 54 in 2004, the median equity was $92,000 and mortgage debt $85,000 (Englehardt, 2006, Table 1).

17. As an example, during the 1980s the number of households in the Cleveland metropolitan area grew by only 18,000, but 46,700 new housing units were constructed, mostly in suburban areas, and unneeded dwellings were left empty in the central city and older suburbs (

Bier & Howe, 1998).

18. We estimated growth after 2000 by comparing data from the 2006 American Community Survey to the 2000 Census.

References

- 1. Achenbaum, W. A. (2005) Older Americans, vital communities: A bold vision for societal aging Johns Hopkins University Press , Baltimore

- 2. http://www.fdic.gov/bank/analytical/fyi/2005/050205fyi.html — Williams, N. 2005. U.S. home prices: Does bust always follow boom? Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Report. Retrieved June 25, 2007, from

- 3. Berson, D., Lereah, D., Merski, P., Nothaft, F. and Seiders, D. (2006) America's home forecast: The next decade for housing and mortgage finance. Homeownership Alliance , Washington, DC

- 4. Bier, T. and Howe, S. R. (1998) Dynamics of suburbanization in Ohio metropolitan areas.. Urban Geography 19:8 , pp. 695-713.

- 5. Birch, E. L. (2002) Having a longer view on downtown living.. Journal of the American Planning Association 68:1 , pp. 5-21.

- 6. Campbell, B. O. (1966) Population change and building cycles. University of Illinois Bureau of Economic and Business Research , Urbana

- 7. http://www.boston.com/news/globe/magazine/articles/2007/03/25/the_real_estate_generation_gap/ — Carmichael M. 2007, March 25. The real estate generation gap. Boston Globe Magazine. Retrieved November 12, 2007, from

- 8. Case, K. E. and Shiller, R. J. (2003) Is there a bubble in the housing market?. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2 , pp. 299-362.

- 9. Chevan, A. (1989) The growth of home ownership: 1940-1980.. Demography 26:2 , pp. 249-266.

- 10. Clark, W. A. V. and Dieleman, F. (1996) Households and housing: Choice and outcomes in the housing market. Center for Urban Policy Research, Rutgers University. , New Brunswick, NJ

- 11. Currid, E. (2007) The Warhol economy: How fashion, art, and music drive New York City. Princeton University Press , Princeton, NJ

- 12. Edmunds, G. and Keene, J. (2006) Retire on the house. John Wiley and Sons , New York

- 13. Engelhardt, G. V. (2003) Housing trends among baby boomers. Research Institute for Housing America, Mortgage Bankers Association , Washington, DC

- 14. Fischel, W. A. (2001) The homevoter hypothesis: How home values influence local government taxation, school finance, and land-use policies. Harvard University Press , Cambridge, MA

- 15. Fishman, R. (2005) The fifth migration.. Journal of the American Planning Association 71:4 , pp. 357-366.

- 16. Florida, R. (2003) The rise of the creative class: And how it's transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. Basic Books , New York

- 17. Frank, L. D. and Engelke, P. O. (2001) Journal of Planning Literature 16:2 , pp. 202-218.

- 18. Frey, W. H. (2007) Mapping the growth of older America: Seniors and boomers in the early 21st century Living Cities Census Series, Metropolitan Policy Program. Brookings Institution , Washington, DC

- 19. Fulton, W., Shigley, P. and Harrison, A. P. (2000) Trends in local land use ballot measures, 1986-2000. Solimar Research Group , Ventura, CA

- 20. Galster, G. C. (1987) Homeowners and neighborhood reinvestment. Duke University Press , Durham, NC

- 21. Gilderbloom, J. I. and Rosentraub, M. S. (1990) Creating the accessible city: Proposals for providing housing and transportation for low income, elderly and disabled people.. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 493 , pp. 271-282.

- 22. Giuliano, G. Land use and travel patterns among the elderly. In Transportation Research Board. Transportation in an Aging Society: A Decade of Experience, Conference Proceedings 27 National Academy of Sciences pp. 192-212. Washington, DC

- 23. Glaeser, E., Gyourko, J. and Saks, R. (2005) Why have housing prices gone up?. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 95:2 , pp. 329-333.

- 24. Gober, P. (1992) Urban housing demography.. Progress in Human Geography 16:2 , pp. 171-189.

- 25. Green, R., Malpezzi, S. and Mayo, S. (2005) Metropolitan-specific estimates of the price elasticity of supply of housing, and their sources.. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 95:2 , pp. 334-339.

- 26. (2007) Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies.. State of the nation's housing, 2007. Author , Cambridge, MA

- 27. Hopkins, L. D. and Zapata, M. A. Hopkins, L. D. and Zapata, M. A. (eds) (2007) Engaging the future: tools for effective planning practices.. Engaging the future: Forecasts, scenarios, plans, and projects pp. 1-17. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy , Cambridge, MA

- 28. http://www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/letter/2005/el2005-21.html — Krainer J. 2005. Housing markets and demographics FRBSF Economic Letter 21. Retrieved November 5, 2006, from

- 29. Lucy, W. H. and Phillips, D. L. (2006) Tomorrow's cities, tomorrow's suburbs. Planners Press , Chicago

- 30. Mankiw, N. G. and Weil, D. (1989) The baby boom, the baby bust, and the housing market.. Regional Science and Urban Economics 19:2 , pp. 235-258.

- 31. Markusen, A. and Schrock, G. (2006) The artistic dividend: Urban artistic specialization and economic development implications.. Urban Studies 43:10 , pp. 1661-1686.

- 32. Masnick, G. S. (2002) The new demographics of housing.. Housing Policy Debate 13:2 , pp. 275-322.

- 33. Masnick, G. S., Di, Z. X. and Belsky, E. S. (2006) Emerging cohort trends in housing debt and home equity.. Housing Policy Debate 17:3 , pp. 491-527.

- 34. McCue, D. and Belsky, E. S. (2007) Why do house prices fall?. Perspectives on the historical drivers of large nominal house price declines Working Paper W07-3. Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University , Cambridge, MA

- 35. Myers, D. (1984) Turnover and filtering of postwar single-family houses.. Journal of the American Planning Association 50:3 , pp. 352-358.

- 36. Myers, D. Myers, D. (ed) (1990) The emerging concept of housing demography.. Housing demography: Linking demographic structure and housing markets pp. 3-31. University of Wisconsin Press , Madison

- 37. Myers, D. (1999) Cohort longitudinal estimation of housing careers.. Housing Studies 14:4 , pp. 473-490.

- 38. Myers, D. (2001) Advances in homeownership across the states and generations: Continued gains for the elderly and stagnation among the young Fannie Mae Foundation , Washington, DC — Fannie Mae Census Note 08

- 39. Myers, D. (2007) Immigrants and boomers: Forging a new social contract for the future of America. Russell Sage Foundation , New York

- 40. Myers, D. and Gearin, E. (2001) Current housing preferences and future demand for denser residential environments.. Housing Policy Debate 12:4 , pp. 633-659.

- 41. Myers, D. and Liu, C. Y. (2005) The emerging dominance of immigrants in the U.S. housing market, 1970-2000.. Urban Policy and Research 233 , pp. 347-365.

- 42. Myers, D. and Menifee, L. Hoch, C., Dalton, L. and So, F. (eds) (2000) Population analysis.. The practice of local government planning pp. 61-86. International City Management Association , Washington, DC

- 43. Nelson, A. C. (2006) Leadership in a new era.. Journal of the American Planning Association 72:4 , pp. 393-407.

- 44. Nothaft, F. E. and Change, Y. (2004) Refinance and the accumulation of home equity wealth Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University , Cambridge, MA — Working Paper BABC 04-10.

- 45. Pitkin, J. Myers, D. (ed) (1990) Housing consumption of the elderly: A cohort economic model.. Housing demography pp. 174-199. University of Wisconsin Press , Madison, WI

- 46. Pitkin, J. and Myers, D. (1994) The specification of demographic effects on housing demand: Avoiding the age-cohort fallacy.. Journal of Housing Economics 3:3 , pp. 240-250.

- 47. Quigley, J. and Raphael, S. (2005) Regulation and the high cost of housing in California.. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 95:2 , pp. 323-328.

- 48. Rosenbloom, S. Mobility of the elderly: Good news and bad news. In Transportation Research Board. Transportation in an aging society: A decade of experience, Conference Proceedings 27 National Academy of Sciences pp. 3-21. Washington, DC

- 49. Shiller, R. J. (2005) Irrational exuberance 2nd ed, Princeton University Press , Princeton, NJ

- 50. http://www.bepress.com/ev/vo13/iss4/art4 — Shiller R. J. 2006. Long-term perspectives on the current boom in home prices. The Economists' Voice, 34, Article 4. Retrieved June 24, 2007, from

- 51. Shiller, R. J. (2007) Historic turning points in real estate Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics, Yale University , Hartford, CT — [Discussion Paper no. 1610]

- 52. (2003a) U.S. Census Bureau.. Public use microdata sample, 5% file: 2000 Census of Population and Housing Author , Washington, DC — [Machine readable data file.]

- 53. (2003b) U.S. Census Bureau.. Statistical abstract of the United States. Author , Washington, DC

- 54. http://factfinder.census.gov/home/en/acs_pums_2005.html — U.S. Census Bureau. 2005a. Public use microdata sample: 2005 American Community Survey. [Machine readable data file.] Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved November 20, 2006, from

- 55. www.census.gov/population/www/projections/projectionsagesex.html — U.S. Census Bureau. 2005b. Interim state population projections. [File 2. Interim state projections of population for five-year age groups and selected age groups by sex: July, 1 2004 to 2030.] Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved October 31, 2006, from

List of Figures

Figure 1. Growth in United States population age 25 and over for each decade from 1960 to 2030 (in millions): Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2003b, Tables 12 and HS-3.

Figure 1. Growth in United States population age 25 and over for each decade from 1960 to 2030 (in millions): Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2003b, Tables 12 and HS-3.

Figure 2. Ratios of median home values to median incomes of household heads aged 30 to 34 in 2000 and 2005, by state: Sources: U.S. Census Bureau (2003a, 2005a).

Figure 2. Ratios of median home values to median incomes of household heads aged 30 to 34 in 2000 and 2005, by state: Sources: U.S. Census Bureau (2003a, 2005a).

Figure 3. Average annual percent of persons buying and selling homes in each age group, for the United States, 1995 to 2000: Note: On average, 8.8% of persons 80 and older sold homes each year.

Figure 3. Average annual percent of persons buying and selling homes in each age group, for the United States, 1995 to 2000: Note: On average, 8.8% of persons 80 and older sold homes each year.

Figure 4. Average annual percent of persons buying homes in each age group, for selected states, 1995 to 2000.

Figure 4. Average annual percent of persons buying homes in each age group, for selected states, 1995 to 2000.

Figure 5. Average annual percent of persons selling homes in each age group, for selected states, 1995 to 2000: Note: On average, between 8 and 9% of persons 80 and older sold homes each year in all these states.

Figure 5. Average annual percent of persons selling homes in each age group, for selected states, 1995 to 2000: Note: On average, between 8 and 9% of persons 80 and older sold homes each year in all these states.

Figure 6. Net annual percent of persons aged 65-69 buying or selling homes, by state and region.

Figure 6. Net annual percent of persons aged 65-69 buying or selling homes, by state and region.

Figure 7. Crossover points: ages at which selling exceeds buying for each state: Note: Shaded states are in the Northeast. Buyers and sellers are owneroccupants, and do not include investors or those buying or selling second homes.

Figure 7. Crossover points: ages at which selling exceeds buying for each state: Note: Shaded states are in the Northeast. Buyers and sellers are owneroccupants, and do not include investors or those buying or selling second homes.

Figure 8. Period in which sellers exceed buyers in each state: Note: Shaded states are in the Northeast. Buyers and sellers are owneroccupants, and do not include investors or those buying or selling second homes.

Figure 8. Period in which sellers exceed buyers in each state: Note: Shaded states are in the Northeast. Buyers and sellers are owneroccupants, and do not include investors or those buying or selling second homes.

List of Tables